Architecture of the Spectacular, the Synthetic and the Belligerent

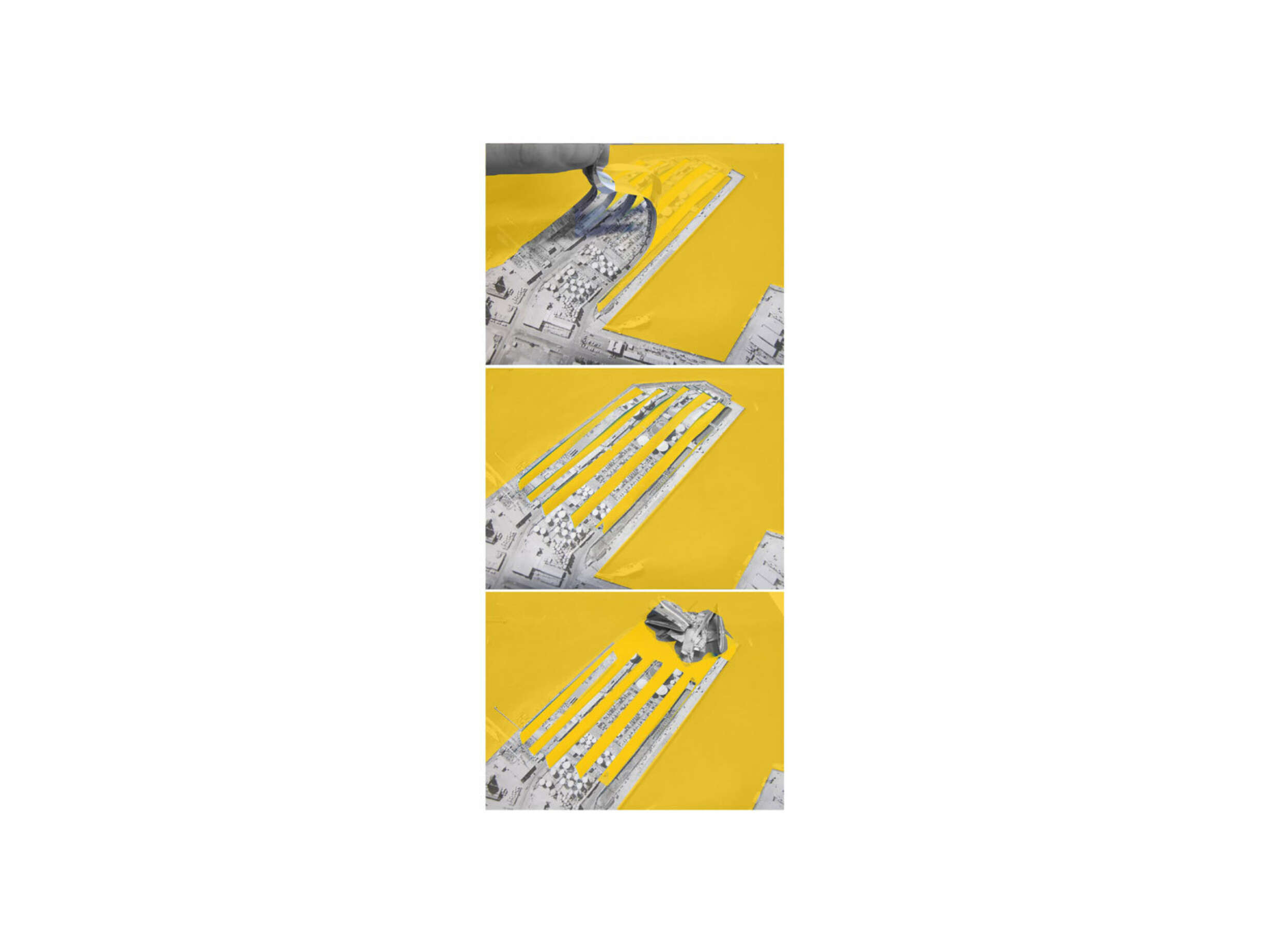

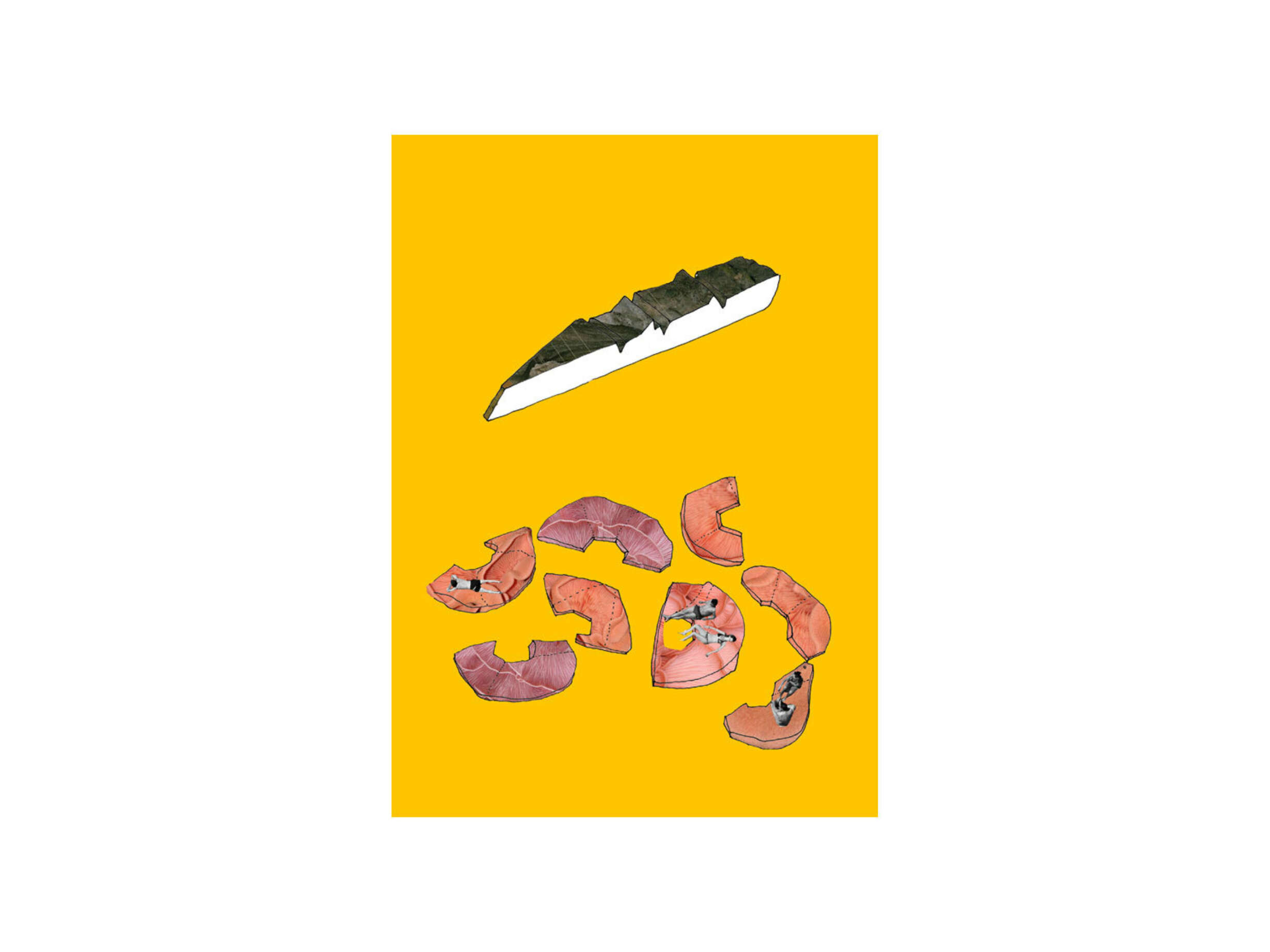

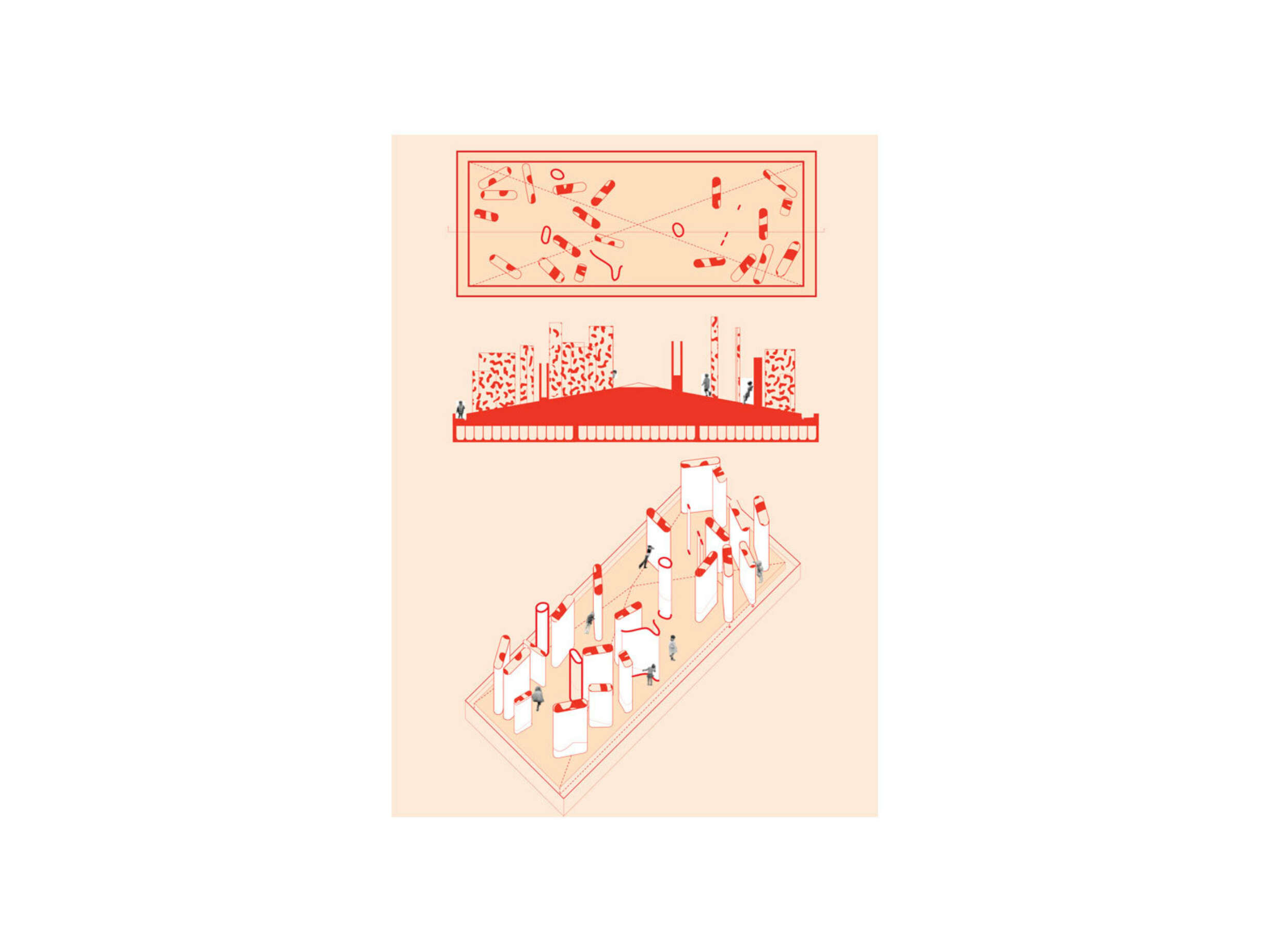

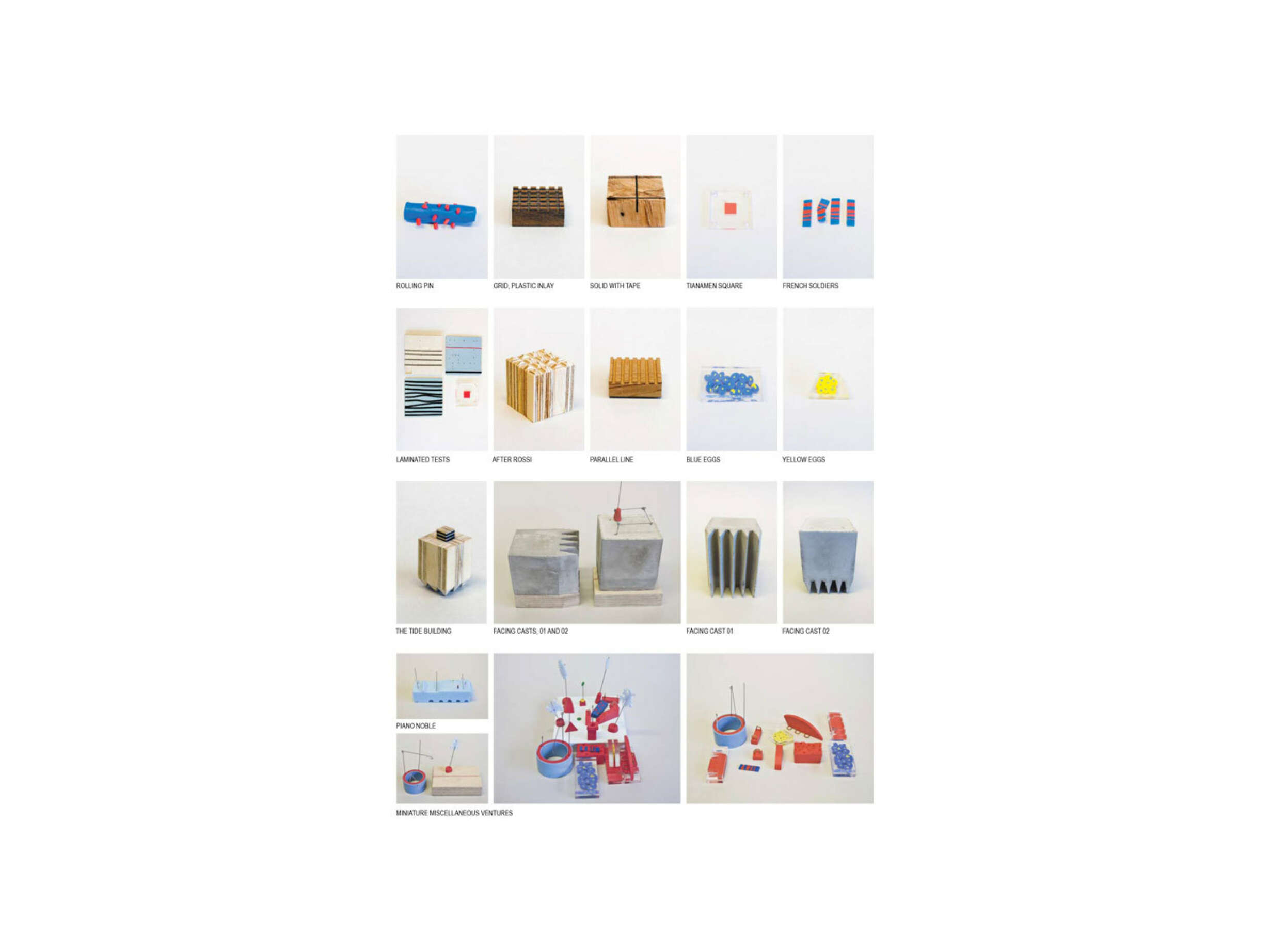

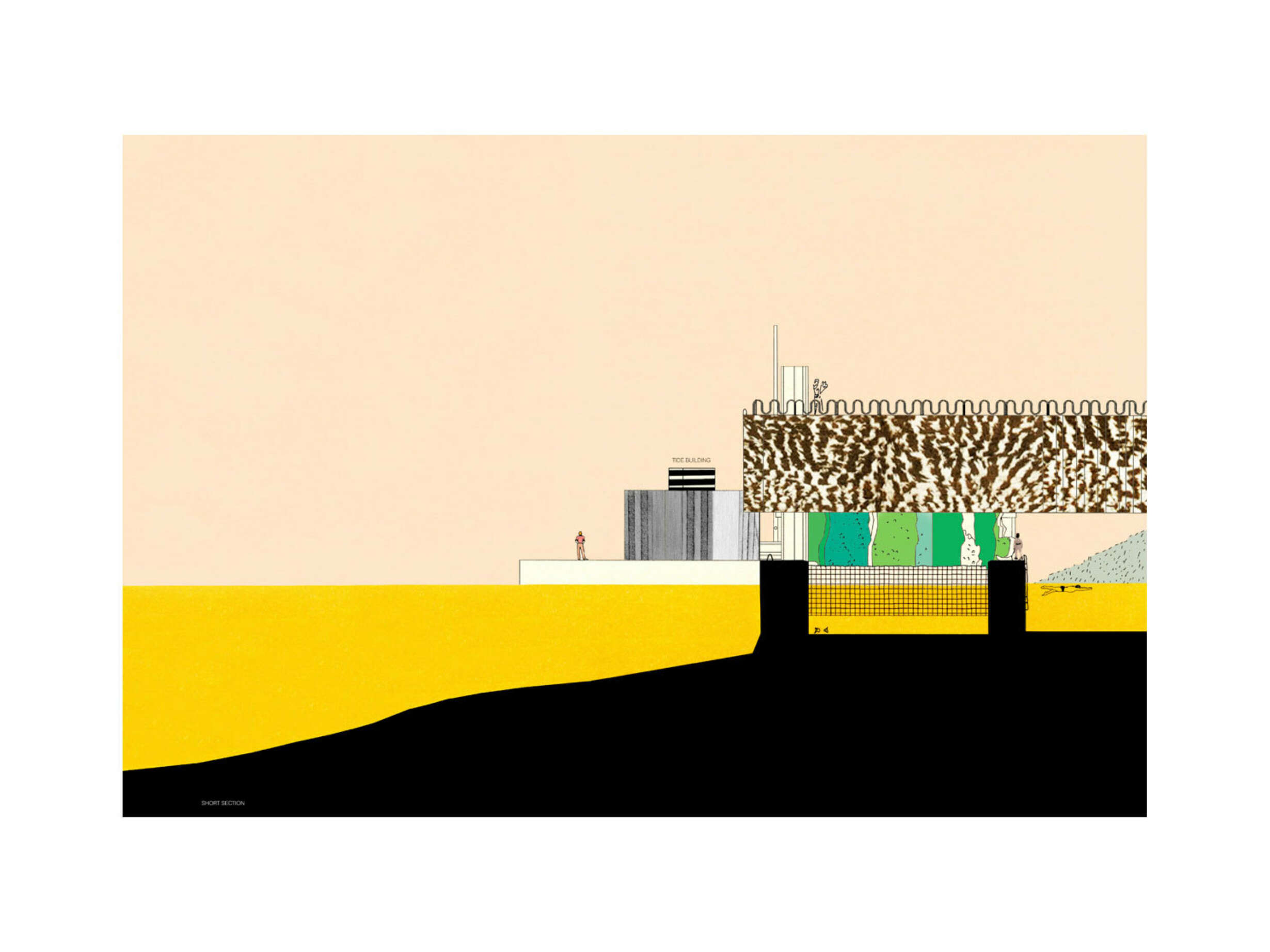

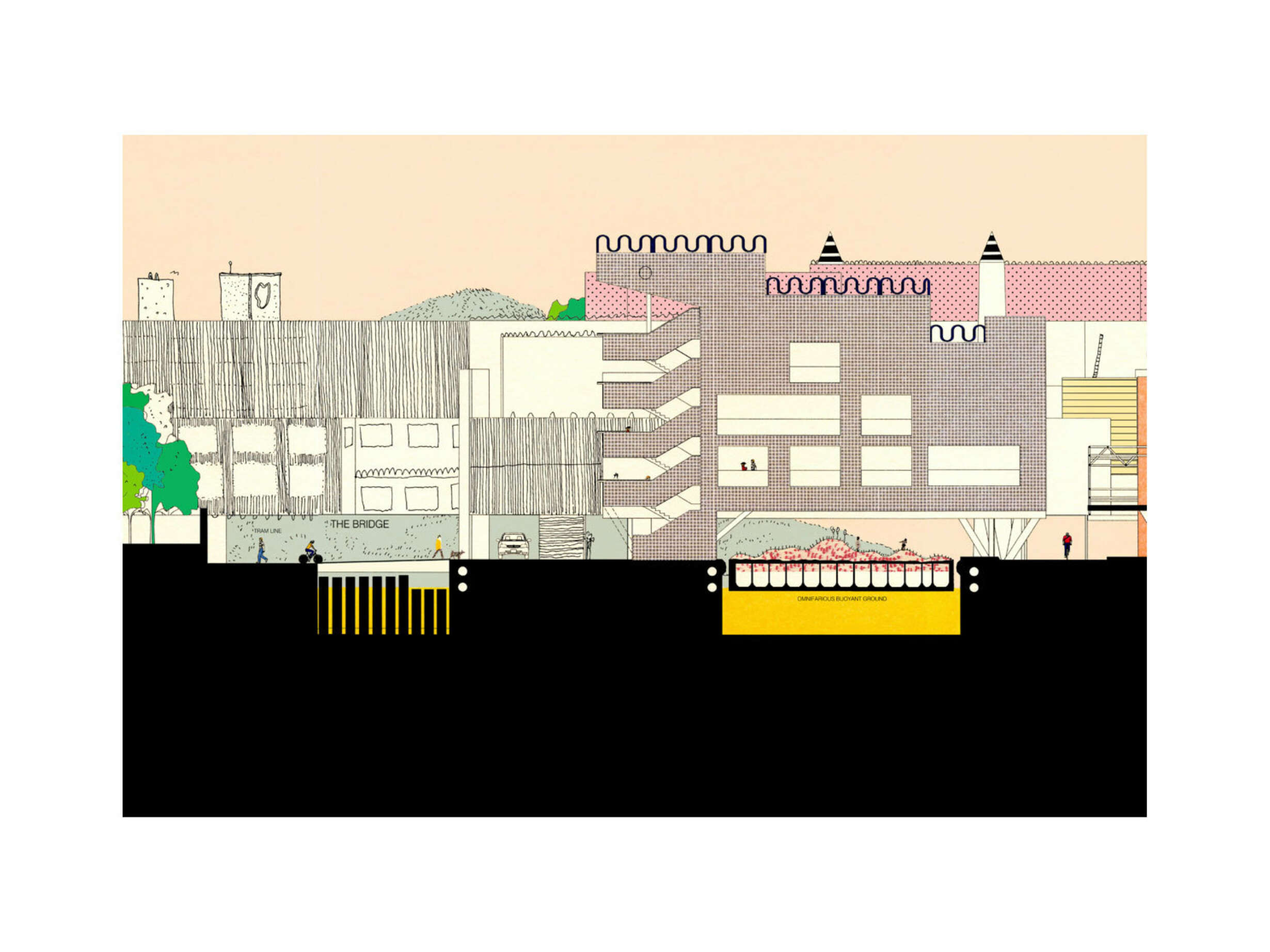

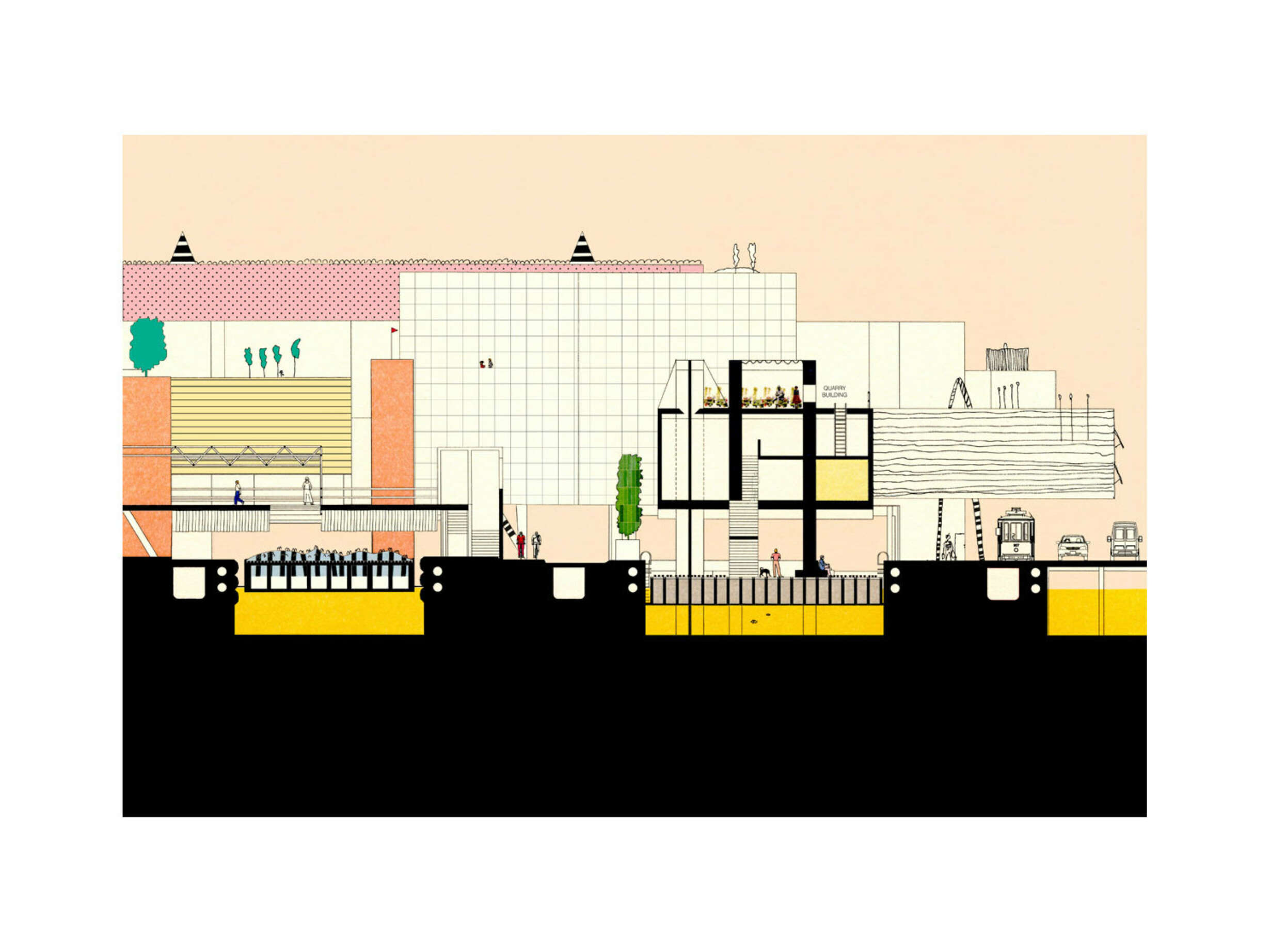

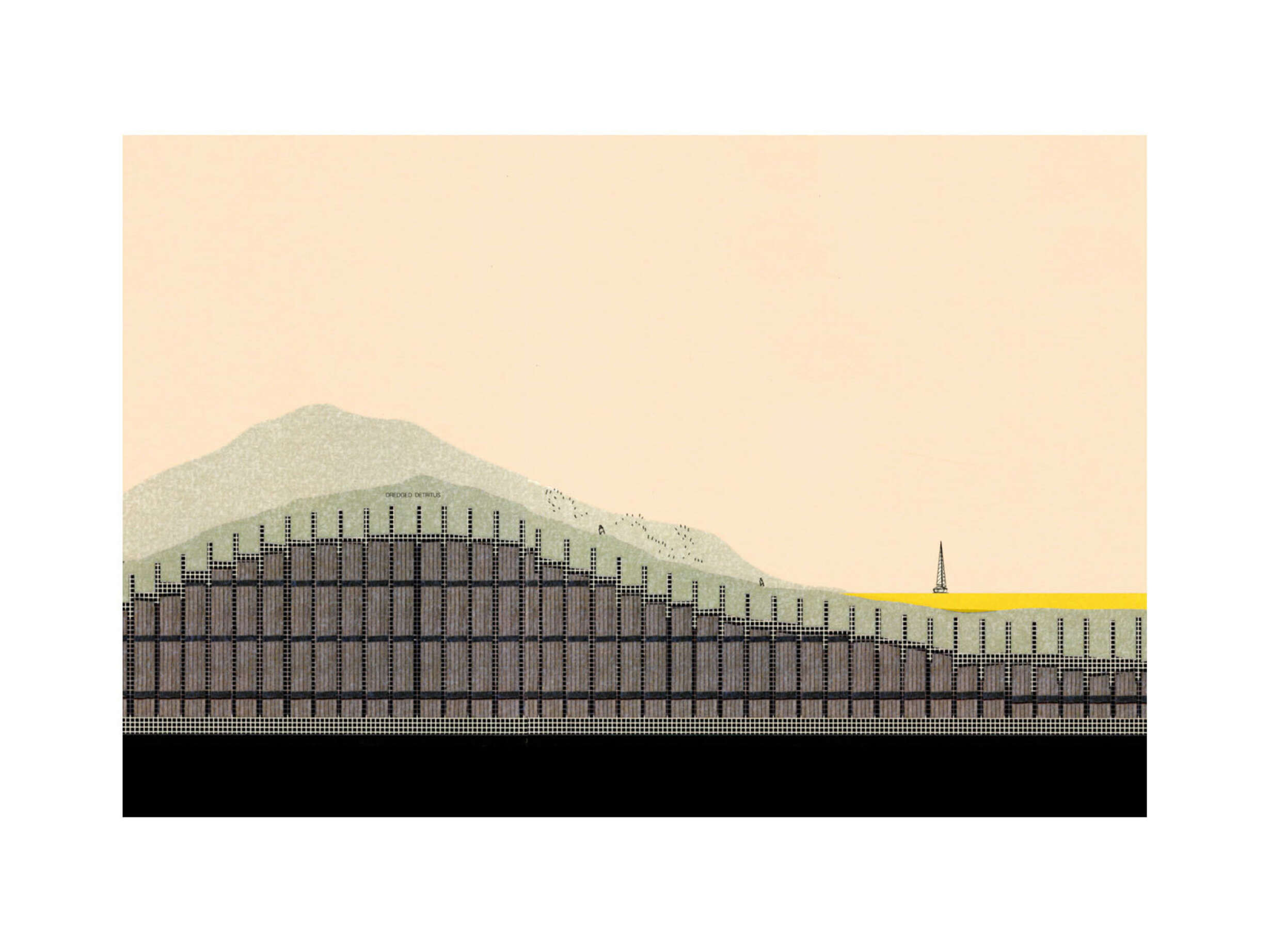

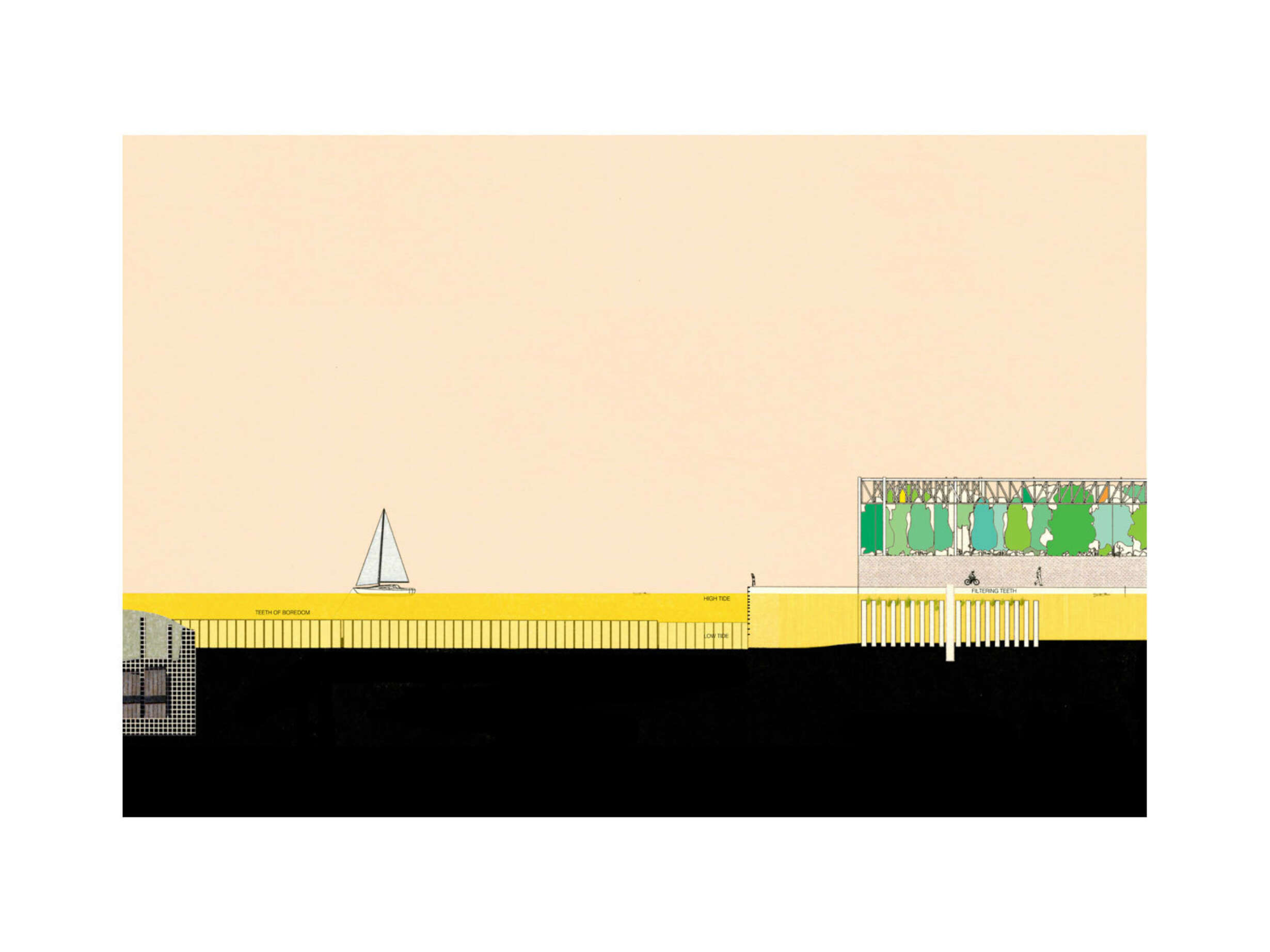

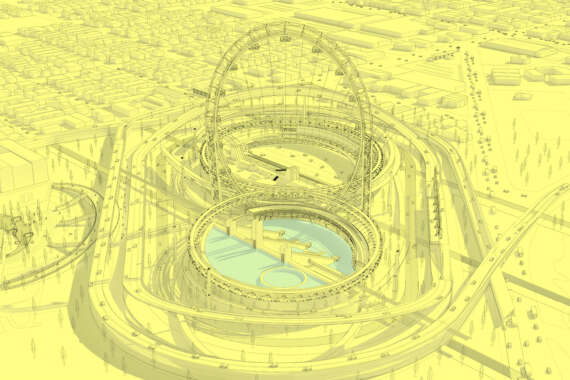

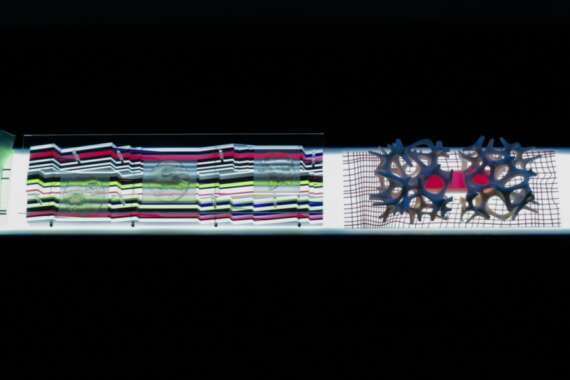

The agenda of Auckland’s leadership in 2012 which aspired towards creating an iconic building on the waterfront similar to those of Sydney, Bilbao or Canary Wharf, was the prime motivation for this thesis. This thesis argues instead for a condition that is vernacular to and therefore unique to Auckland. Given this disposition towards the iconic, this thesis sought to mine other architectural precedents that have negotiated the intricacies of water, surface and resilience. These precedents reside in research titled Architecture of the Spectacular, the Synthetic and the Belligerent. Informed by these precedents this thesis speculates through a designed intervention in Wynyard Point a reconciliation of Auckland City’s relationship to the Waitematā Harbour.

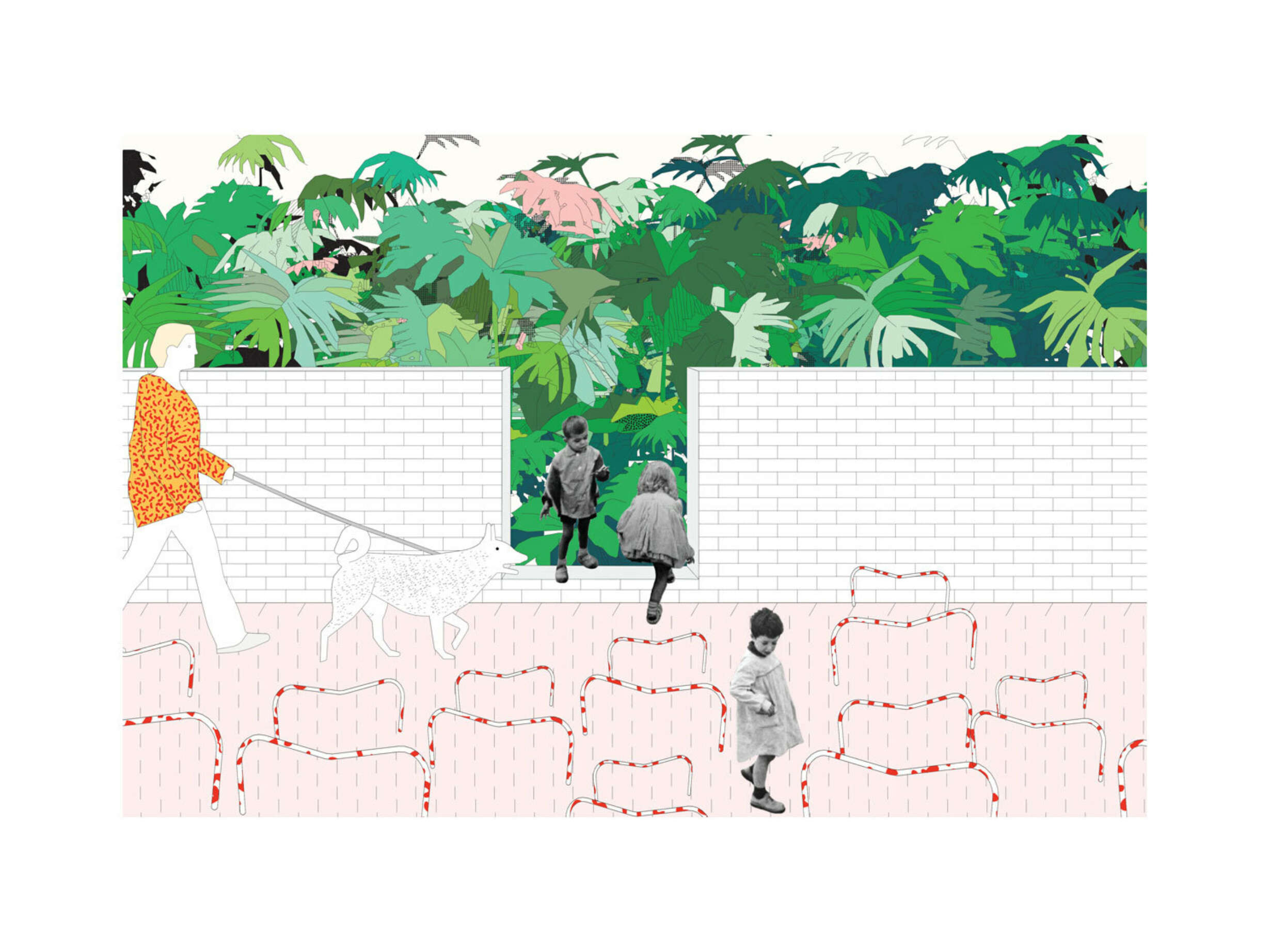

This once private, reclaimed peninsula is re-appropriated through a seascape island and a mutable urban littoral. It contends with the accumulated history of Auckland’s reclaimed land, perceived ownership and the ever contentious issue of public and private access. It tests the propensity of an architectural landscape hybrid to capitalise on the opportunities the post-industrial port affords. This affordance resides with sea and its tides, and encourages a hybridity between disciplines and historical precedent to project opportunities inherent in the context of Wynyard Quarter. This, in an era by which capital, return on capital and consumption are the drivers of redevelopment. The large scale redevelopment of any place is faced with the underlying corporate demand for an iconic architecture, one that is capable of branding, thus creating an image of the new place acceptable to these corporate interests. This thesis proposes instead an iconic edifice, a symbolic island and public urban littoral that is constructed by architectures of the spectacular, the synthetic and the belligerent.